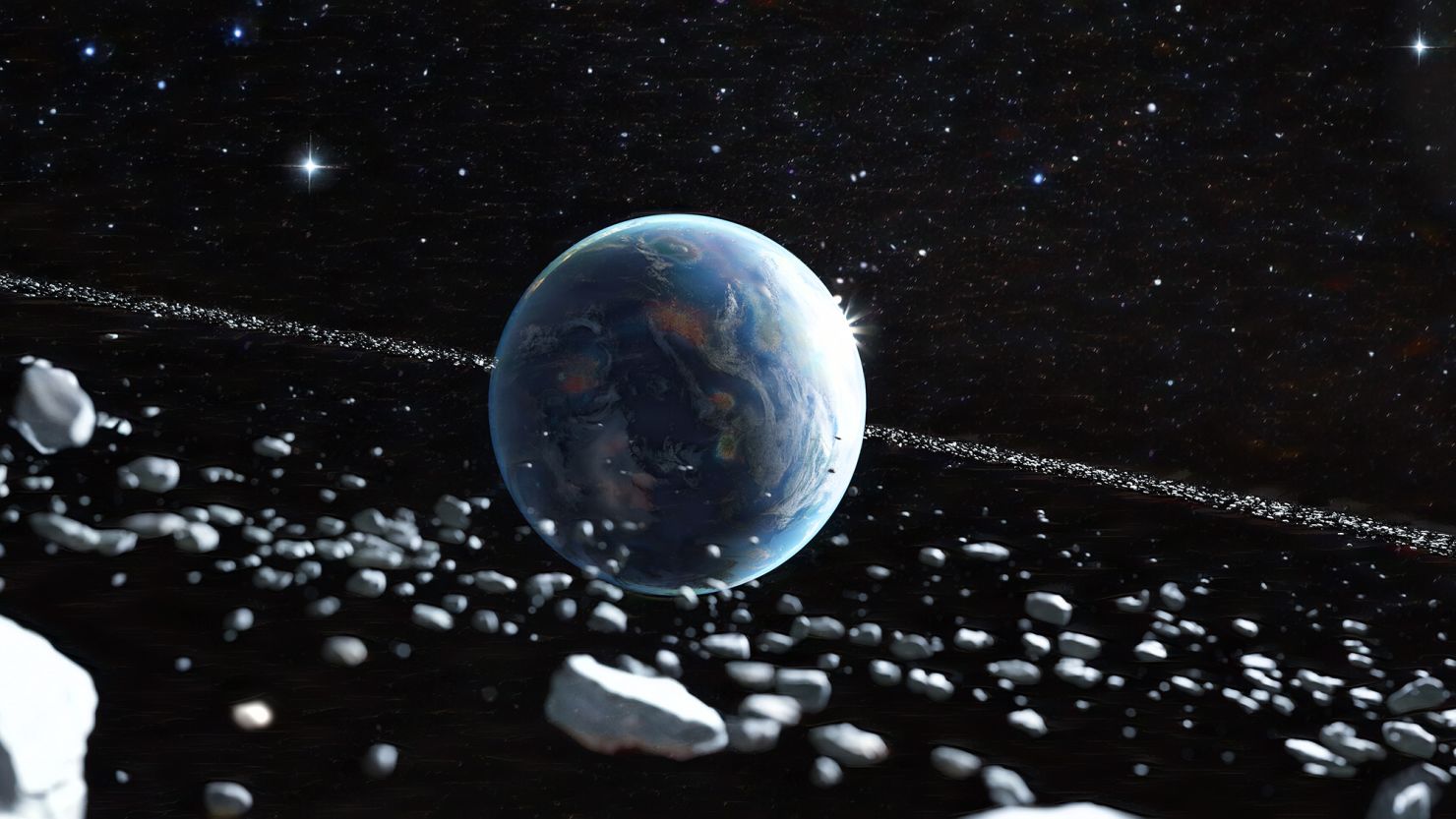

Famously known for its extensive ring system, Saturn is one of four planets in our solar system that have the distinctive feature. And now, scientists hypothesize that Earth may have sported its own ring some 466 million years ago.

During the Ordovician Period, a time of significant changes for Earth’s life-forms, plate tectonics and climate, the planet experienced a peak in meteorite strikes. Nearly two dozen impact craters known to occur during this time were all within 30 degrees of Earth’s equator, signaling that the meteoroids may have rained down from a rocky ring around the planet, according to a study published September 12 in the journal Earth and Planetary Science Letters.

“It’s statistically unusual that you would get 21 craters all relatively close to the equator. It shouldn’t happen. They should be randomly distributed,” said lead author Andrew Tomkins, a geologist and professor of Earth and planetary sciences at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia.

Not only does the new hypothesis shed light on the origins of the spike in meteorite impacts, but it also may provide an answer to a previously unexplained event: A global deep freeze, one of the coldest climate events in Earth’s history, may have been a result of the ring’s shadow.

Scientists are hoping to find out more about the possible ring. It could help answer the mysteries of Earth’s history as well as pose new questions about the influence an ancient ring could have had on evolutionary development, Tomkins said.

A Saturn-like ring on Earth

When a smaller object gets close enough to a planet, it reaches what’s known as the Roche limit, the distance where the celestial body has enough gravitational pull to break apart the approaching body. The resulting debris then creates rings around the planet, such as those around Saturn that may have been formed by debris from icy moons, according to NASA.

Scientists previously believed that a large asteroid broke apart within the solar system, creating the meteorites that hit Earth during the Ordovician Period. However, such an impact would have likely caused the strikes to be more randomly distributed, such as the randomization of the craters on the moon, Tomkins said.

The study authors hypothesize that a large asteroid, estimated to be about 7.5 miles (12 kilometers) in diameter, instead reached Earth’s Roche limit, which might have been about 9,800 miles (15,800 kilometers) from the planet based on the measurements of past rubble-pile asteroids. The asteroid would have been largely beat up from other collisions, making rubble loose and easy to pull apart by Earth’s tidal force, Tomkins said.

The ring would have formed along the equator due to Earth’s equatorial bulge, similar to how the rings of Saturn, Jupiter, Uranus and Neptune are also around each of those planets’ equatorial planes, he added.

About 200 impact strikes from throughout Earth’s history are known, Tomkins said. By looking at how Earth’s landmasses moved over time, the authors found that the 21 known craters dated to the Ordovician Period were all near the equator. Furthermore, only 30% of Earth’s land surface suitable for preserving a crater was near the equator. If the impacts were random instead of from a ring, most of the craters should have formed away from the equator, he added.

The authors also point to a February 2022 study that analyzed impact craters on Earth, the moon and Mars, and found signs for the Ordovician impact spike only on Earth, further adding evidence that aligns with the ring theory.

“The paper presents a pleasing idea that ties together a few mysteries,” said astrophysicist Vincent Eke, an associate professor in the Institute for Computational Cosmology at the UK’s Durham University who was not involved with the new study.

The research analysis found several deposits across Earth from the same period as the impact craters containing high levels of L chondrite, a common meteorite material, that had signs of shorter space radiation exposure than meteorites found today. The finding suggests that a large, space-weathered asteroid that likely strayed within Earth’s Roche limit broke up near the planet, the study authors wrote.

A few million years following the period of increased meteor strikes, about 445 million years ago, there was a dramatic decrease in Earth’s global temperatures known as the Hirnantian Age.

“The subsequent debris from such an event (a potential ring) could account for these three observations,” Eke said in an email, referring to the impact craters, meteorite debris and global climate shift.

The study authors are researching what extent of shade would be needed to cause a deep global freeze, a finding that in turn could help estimate how opaque the ring was, Tomkins said. Similarly, Earth could have been cooled by clouds of dust from the meteorite impacts, he added.

Tomkins said he hopes future research will establish how long the ring persisted and shed light on how it could have influenced the evolutionary changes that Earth faced most likely due to challenging climatic conditions. “Understanding the causes of Earth’s climate change can help us think about (the) evolution of life as well,” he added.

It’s difficult to say what such a ring would have looked like without knowing the density of the material, but Tomkins estimates that even a faint ring would have been visible from Earth.

“If you were on the night side of the Earth looking up, and the sunlight is shining on the rings, but not on you, that would make it probably quite interestingly visible — it would be quite spectacular,” he said.

The possibility of future rings

Based on the duration of the global cooling period and the dating of the craters and meteorite material, Earth’s possible ring could have lasted 20 million to 40 million years, Tomkins said. Collisions between other particles would have caused space rocks to be thrown out of the ring.

Previous research found that ancient Mars might have also sported a ring, or rings, and scientists predict that planet may one day have more in the future.

“While rings are associated with the outer, giant planets in the solar system at the present time, in the next 100 million years or so, Mars should acquire a ring system when its inner moon, Phobos, spirals inside the rigid Roche radius and is itself torn apart,” Eke said in an email. “Thankfully, for the development of life on Earth, these types of (events) are rare at the current time!”

Since late September, an asteroid named 2024 PT5 has been traveling near Earth. The space rock is commonly referred to as a “mini-moon” due to it coming within 2.8 million miles (4.5 million kilometers) of the planet. However, even during the asteroid’s closest pass to date on August 8 at about 352,300 miles (567,000 kilometers), it was nowhere near Earth’s Roche limit, said Carlos de la Fuente Marcos, a researcher on the faculty of mathematical sciences at the Complutense University of Madrid who has studied the mini-moon. De la Fuente Marcos was not involved in the new study.

Also, the suggested Earth ring would have “had to be the result of the disruption of a much larger body as the authors indicate in their paper,” he added in an email, so the asteroid, likely about 37 feet (11 meters) in diameter, could not have made a new ring for Earth.

“You’d need to capture a big one and get it into exactly the right orbit to break up. … (This mini-moon) is just an example of the processes that go on in our near space area that can lead to the sort of thing we’re talking about,” Tomkins said. However, “this ring formation event we think may have happened only once in the last 500 million years.”